Yasujiro Ozu had a great feel for seasonal nuance. His Early Spring, Late Spring, Early Summer, The End of Summer and An Autumn Afternoon, gave voice to subtle distinctions that pervade his many films, including those without seasonal labels. The last two titles were also Ozu’s final two films. They have always seemed particularly poignant—the final statements of one of Japan’s most accomplished directors. To life-long academics, this particular shift is a familiar if more mundane one, heralded by the autumnal advances of the new academic year, in the face of the lingering experiences of summer. Like Pavlov’s stimuli, the rituals of the impending season trigger well-rehearsed responses that slowly but surely tip the perceptual frame. We go back in medias res, in the middle of things. The distinctions are as fine-grained as Ozu’s, even though the triggers are sometimes just as paradoxically dramatic.

The build-up for this fall actually started last spring with the admission of our 11th graduate class, and the addition of Sasha Constanza-Chock to the CMS faculty and Ethan Zuckerman to the Center for Civic Media. Grant renewals for Civic Media, a funding extension for GAMBIT, new support for The Education Arcade and HyperStudio, and the inclusion of a new research group—the Mobile Experience Lab—into CMS all contributed to a growing sense of anticipation and excitement. Fortunately the rituals of summer—such as the arrival of GAMBIT’s Singapore interns and wonder of seeing finished games emerge from research; or the altered work routines of the CMS staff, which this year included expanding our office space into the Media Lab’s “Pond”—kept us from getting ahead of ourselves. Summer was full enough to generate its own distractions—quite a task considering the steady build-up for fall! But the actual arrival of the students, visiting scholars, the transitional rituals marked by the CMS orientation, and the finishing touches on syllabi, the colloquium line-up, and the newsletter…all combined inexorably to shift the delicate balance away from late summer.

Despite the longue durée rhythms that seem to govern these events, this year has had its share of differences. A one-year hiatus in the graduate program means that there are no seasoned second-year students on hand to welcome and share their collective wisdom with the incoming class. And as the program’s reorganization process enters its third and, we all hope, final year, for many of the faculty, the continuity of meetings and discussions undercuts any sense of seasonal undulation. If anything, the pastoral cycles of recurrence and change celebrated by Ozu and routinized in the academic calendar, for this cohort anyway, have been overwritten by a far more linear trajectory.

The ongoing reorganization has yielded much of interest to students of institutional behavior. And it has, at least for some, generated a new empathy for the challenges facing our colleagues in the media industry, caught as they are, in the face of fast-changing conditions, between the competing logics of stability and transformation. In fact, some of the debates sparked in our reorganization serve as powerful reminders that, generally speaking, the university has been blissfully isolated from the seismic changes taking place in culture at large. Our ritualistic use of medieval garb; our disciplines, some of which hearken back to the Trivium and Quadrivium; and our organization of study, which largely reflects the needs of the industrial age, all offer a reassuring sense of continuity and tradition, an anchored position from which to assess ongoing change.

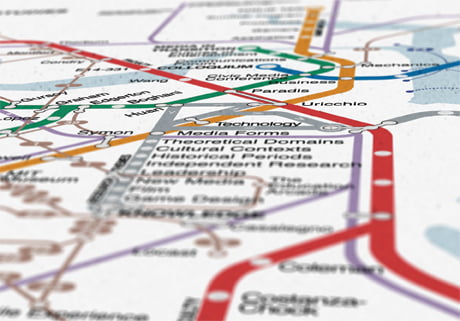

This legacy view has many affordances, and media studies have made good use of them. Yet, for a program like ours, the situation is complicated. CMS seeks to understand the dynamics of media change. We want to train people who can make sense of and lead that change as it plays out across an array of cultural practices. Comparativity offers a useful methodology but also requires that we move across disciplinary traditions with agility. This movement, characteristic of media studies generally—but also women’s studies, American studies, and more—fits awkwardly with the disciplinary tradition. On one hand, we “studies” programs make use of the good work of our more disciplined colleagues, and on the other, our strength comes precisely through our ability to combine approaches and develop strategic responses outside the domain of any one discipline. CMS has gone a step further and embraced a non-disciplinary stance, permitting us to ask unexpected questions and discern long unrecognizable patterns. More a principle than an entity, CMS was, for its first decade, a logic that linked specialists across disciplinary and departmental bounds. With the reorganization, we face the challenges of reification—of becoming a thing—great for program sustainability, challenging for our program’s remit.

Might this shift, too, be read in terms of a seasonal metaphor? And if so, where in the calendar are we? That will take some time to ponder, but regardless, one of Ozu’s great lessons regards embracing and savoring the process of change.