Digital simulations offer learning opportunities to engage and reflect on systemic issues of racism and structural violence against communities of color. This talk examines how natural language processing tools can be used to better understand participants’ experiences within simulated environments focused on anti-racist teaching and identify changes in participants’ behavior over time. As K-12 schools increasingly reckon with our country’s long history of racist teaching practices, digital simulations may provide ways to help teachers name, re-examine, and reflect on their own practice and move toward anti-racist teaching.

Dr. Joshua Littenberg-Tobias is a Research Scientist in the MIT Teaching Systems Lab. His research focuses on measuring and supporting learning within large-scale technology-mediated environments with a focus on civic engagement and anti-racist teaching practices. He received his Ph.D. from Boston College in 2015 in educational research, measurement, and evaluation.

The following is a transcript generated by Otter.ai, with human corrections during and after. For any errors the human missed, please reach out to cms@mit.edu.

Vivek Bald 00:47

…everybody to CMS colloquium. And as most of you probably know, but it bears repeating for those guests, attendees, that the way that we run the colloquium is that we have our graduate students and other members of the MIT community, on screen with our guest. And after the presentation, there’ll be a q&a in which folks on screen can directly ask questions, and those who are attendees off screen can ask questions versus via the q&a or so that is very much encouraged. So tonight, I am going to hand over to my colleague, Justin Reich, to introduce our guest, Joshua Littenberg-Tobias. Great.

Justin Reich 01:43

Thanks so much, Vivek. And thanks, everybody for being here. So we make media as a society for many purposes, we make media to entertain, we make media to persuade, we make media to inform. And one of the things we do is make media to educate, to help people build new capacities that they didn’t have before. And there are lots of disciplines that can contribute to the study of media that educates. And the learning sciences are kind of a bundle of those differences connected to psychology and cognitive science that are interested in particularly in sort of technology inflected ways, like how do we create media that most effectively build new capacity. And so Josh, and I work in a lab, the teaching systems lab, which is really interested in these questions of how do we help people learn better? Josh has specialties in measurement and evaluation, there are lots of different ways to improve media for education. And one of those ways to improve media education is to figure out whether or not the things you’re doing are working. Are if you if you say that you want to create media that helps teachers do a better job with anti racist teaching. What does that even mean? How would you figure out whether or not your media is doing the things that you want it to do?

But and you can ask the same question of if you make media, you know, that helps kids, you know, learn to divide fractions or adults to be able to conjugate Spanish verbs, how do you know whether or not what you’re doing is really working? How do you know whether or not it’s working better than something else. So that’s the that’s the expertise that Josh brings to our interdisciplinary lab. And we’ve been doing some really cool work together over the last few months to figure out how we can help support teachers doing a better job with equity teaching practices, and Josh has come up with some really innovative ways to help us figure out how we’re doing using a combination of quantitative and qualitative and computational approaches. So I’m really excited to turn it over to Josh to let you all learn more about the work that he’s doing with bar beds and many other folks in the lab. Oh, I wanted to say one other thing, which is that Josh has some job talks coming up for some faculty positions he’s applying for. And this is a bit of a practice for one of them. And it’s actually quite an interdisciplinary audience at this other talk that he’s giving. So you all should feel very free. To be very candid in your criticism of Joshua’s talk both on the substance, and on the delivery of their stuff that doesn’t make sense or you think doesn’t land well, it’d be very generous of you to let him know so he can improve on those things before the before the live event coming up. So over to you, Josh.

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 04:37

Thanks, Justin. I appreciate the introduction. I just wanted to say before I jump into it, that this is work that I’ve been really honored to be involved with. And I’ve worked with a lot of really great people at the MIT systems lab, including Elizabeth Borneman, who was a graduate student at CMS last Marvez who I’ve worked with for a number of years, Chris Buttimer, who’s a postdoc, and many, many other people who’ve contributed to this research. And so a lot of what I’m doing some of it, a lot of it, I couldn’t have done it without the help and support and working with other people. So I’m going to share my screen. And we will get started. So my talk today is on measuring equity promoting behaviors and digital teaching simulations. And to talk a little bit how I use topic modeling, which is a form of natural language processing, understand what’s happening in the simulations. But before I kind of dive into the specifics that I did, I need to give you a little bit of background about teaching and education to give you kind of like the 3000 foot view to sort of understand kind of what we did and why. So just to kind of go over how the top of the structure, I’ll start with some background about the topic and sort of why we looked at the things that we did us talk about, what are digital equity teaching simulations, there’s a lot of a lot of words there to unpack.

Then I’ll talk about the specific analysis that I did using something called structural topic modeling. Now, it’s been a little bit about how the kind of the inside the hood, how that actually works in practice. And then I’ll present some results from a analysis that I’ve worked on over the last couple months looking at a course that we administered last spring. And finally, I’ll present some, some future directions about where I see this research going over time. So just start just some background. So many of you have heard of the term, the achievement gap. So this is a term that’s very commonly used in education policy circles. And it refers to the difference in achievement between white and Asian students, and black and Hispanic and Native American students. And so this is something that policymakers have been talking about, you know, for a long time, particularly since the 1980s. And they’ve been all kinds of education reform efforts to close the achievement gap. I know some of you may have heard of No Child Left Behind, which was under President Bush, then there was Race to the Top with Obama and the to 2010s. And then there was the Every Student Succeeds Act, and 2014. So we’ve had all these iterations of forum. But the thing is, there hasn’t been a change.

So if you look at this graph that I’m presenting, you see that the achievement gap has pretty much remained constant over time since early 90s. So with all the education reform doing, there hasn’t actually been changed and achievement gap. And, in particular, in the last few years, there’s been a lot of criticism, even the term the achievement gap, there was a research that came out last summer that actually showed that if you kind of frame that you show people videos about negative stereotypes about African American students. And there is a lot of criticism about framing the achievement gaps, framing distance in terms of a gap. And, and the reason for this is that by talking about the gap, many people attribute that to the actual characteristics of the students themselves, and now to the opportunities that students have experiences students have in school. And so by by focusing on sorting outcomes, you’re ignoring all the inputs and all the experiences that students are having that lead to these differences in academic achievement. And so in our work, we we often draw on the work of a scholar called, named Richard Milner who talks about this idea of the opportunity gap. So in his work, he says that we really need to focus not just on, like achieving outcomes, which are important. We don’t want to ignore differences outcome. But it’s also really important to understand the reasons for those differences. And his work. In his work. He talks about all the ways that schools are systematically discriminated against, particularly black and Latinx students, and all students of color in the way that schools are structured. Who do students have teachers who look like them? What are the dominant cultures within schools? How do schools rules and policies, how do they affect students and there are many, many other ways including curriculum that is not culturally responsive and standardized testing that doesn’t capture all of students abilities. So these are all factors. In this talk I’m going to talk to, I’m going to focus on one specific aspect of this, which is this idea of discretionary spaces in teaching. And this idea comes from the work of Deborah ball, which basically said that in teaching, teachers have a lot of things that they can’t control, you know, often they can’t control when school happens, they can’t control. You know, what their classroom history look like, what type of building they’re in. But anyone who has been teaching knows that there are a lot of decisions that teachers have to make every day and that these decisions can have a big impact on students experiences. And in her research, she talks about kind of really examined needs, especially in spaces and understanding what are the forces that affect what teachers decided to do?

And increasingly thinking about how did these discretionary spaces either perpetuate or disrupt racism and racist structures. So for example, if you have teacher sees a student who has their phone out, they have a number of different choices of what to do, they can just ignore it and keep on teaching, they can, you know, go unnoticed, and say, hey, you’re not supposed to your phone out, they can confiscate their phone, they can send the student out. And so the principal and all these students have have implications further down the line. We know from research, that discipline in school is connected to the school to prison pipeline. So even though you think of this as a sort of individual like, decision, all of these things accumulate and add up over time. So I’m gonna kind of transition now to talking about our digital equity teaching simulations. So in these simulations, what we’re trying to do is we’re trying to capture practicing these discretionary spaces. And I wanted to give you some examples of what this looks like in practice. So this is from one of our simulations called Jeremy’s journal. And to give you a little background on Jeremy’s Journal, in the simulation, you play the role of a teacher who is has a student named Jeremy and Jeremy is at sometimes very actively engaged in class and other times disengaged, he’s generally very friendly and social, but sometimes struggles to kind of focus on the actual side of things supposed to be doing. And one day, he misses class and for in, you don’t can reason why in this class, and the next day, he comes to class, and he presents this note from his mom. And then he says, I’m sorry, I was out yesterday, I wasn’t feeling great and had to go home. What do you want me to do for makeup work? And he presents this this note from his mom. And the thing is that the school policy, you know, is that you have to have a note from a doctor. So in this moment, what do you do? response one is say, We missed you at class, just you guys hope you’re feeling better, or response to remember that the school policy is that need to sign doctor’s note in order to be excused from class. Now, I was wondering if I wanted to try something, we’ll see how it works. I’m going to send out a poll, I only want you to answer the first question.

But I want you to say, which of these two responses would you choose? One, we missed you at class yesterday, or to remember the school’s policies that can be assigned doctors, no more to be excused from class. So you just need to answer the first question. Hey, everyone, see the poll? Let’s see. Panelists? Okay. Okay. If you can’t vote, you just put either one or two in the chat for which one you would do. Okay, I’m seeing a lot of a lot of ones. So I think we have an agreement. Many people. Yeah. I think everyone’s panels, okay. So that’s good to know that, that that technology is not particularly reliable. Um, so I’m seeing it seeing a lot of one. So these are actual responses that people gave in the simulation when we did this at the course. So these actually represent two different ways that people can respond to the situation. And what we’re trying to do with these scenarios is capture these individual Moments of teaching and provide people with options like, What do I do? What would I do in this moment? And once you do that give them time to reflect on why am I making the choices that I’m making? Are these choices actually? Are they perpetuating racism? Or are they disrupting it, so what why simulations. Um, so simulations have a number of affordances, that make them particularly useful for talking about thinking about teaching. One of them is actually some, you might see it as a limitation, which is that in a simulation, you are representing some parts of reality, but not all of it. So simulation, by definition is not capturing everything about our real life teaching situation. But in some ways, it actually works to our advantage for teaching. Because teaching is extremely complex activity, anyone who’s ever sit in front of a class of students knows that there’s a lot going on at any particular moment. And so what we’re doing in our simulations is we’re breaking it down into simpler parts in order to focus people’s attention on particular things. And so it allows you to really focus on discrete aspects of moves and teaching, rather than having to try to kind of comprehend a large situation where lots of things are happening at the same time. Another thing that is particularly good about simulations is that it allows you to practice those within a kind of simplified lower stakes setting. And this is particularly good for novices who might not be ready to take on sort of a more complicated situation and might benefit from doing things in a lower stakes, simplified environment.

But even for more experienced teachers, it’s often helpful to take a step back and kind of be reflective and think about, okay, now that I’m out of a classroom no matter what I actually do in this situation, and they think about it and talk about it. And the final thing that is helpful with simulations is that it allows you to kind of provide opportunities for targeted reflection and feedback. And I use the term target to hearing intentionally, because one of the things we know about learning new skills is that it doesn’t necessarily help to kind of do the same thing over and over and over again, what what allows you to improve is to say, do you have deliberate practice focusing on a specific skill set and getting feedback on that skill set. So what we’re trying to do in our simulations is really be very intentional focus on specific things, and using those for opportunities for reflection and feedback in order to facilitate learning. So I’ve kind of set up like what like some of the background about influencing our work, I talked about why simulations now I wanted to talk a little bit about actual types of simulations we built. So the teaching system lab has developed a platform called teacher moments, I know, many of you are familiar with teacher moments, either through the teacher systems lab, or edtech, design studio are just sort of being around the CMS department.

But what’s really cool about teacher moments is that it’s a platform for authoring simulation, so anyone can go and build their own simulations and teacher moments. It’s free, openly licensed, people can use it however they want. And we’ve had more than 300 scenarios authored within teacher moments and have had more than 6000 users and more and more people are using it every day. So I definitely encourage you, if you’re interested to check out teacher moments to kind of see sort of some of the features to that. I wanted to give you a flavor of what a scenar-, what a teacher moment scenario actually is, like, many times we talk about these simulations, people assume, oh, you’re doing something in VR, or you’re doing something that’s sort of, you know, different from what it actually is. And so I think it’s helpful to actually kind of see what a simulation looks like. So I’m going to play about a three minute clip from one of panelists share computer sound, so you can hear it. So this is a clip from one of our simulations called roster justice. And the background to this is in this simulation, you play a teacher who a few weeks before school, you get your your class roster. And you notice that the computer science class that you’re supposed to that you’re supposed to teach the rosters are imbalanced. So even though your school is 50%, African American and Latin x, the actual composition, the class is mostly white and Asian and male students. And so you go to the principal Mr. Hall, who is played by Justin In this scenario, you’re going to have a conversation with him about your class rosters.

Justin Reich 19:53

As you come in, I wanted to talk with you about some of the scheduling changes and I also heard that you wanted to talk to me got someone else coming in a few minutes. So why don’t we cut to the chase while you lay it all out for me.

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 20:06

Thank you, Mr. Holl for meeting with me, I know that you have a busy schedule. Before we talk about the scheduling changes, I just wanted to share my concerns. I looked over the rosters for computer science, and I noticed that the computer science class doesn’t reflect our student population. It has way more white students and male students than we have in the rest of the school. And I’m concerned that it means that our students of color, and our female students are missing out on some opportunities to take computer science. So can we talk a little bit about how we might be able to change the schedule so more students can take computer science?

Justin Reich 20:52

Well, first, I’d like to say thank you for bringing the issue to my attention. I get your concerns really I do. Unfortunately, there’s not a lot that we can do. School is starting just three weeks from now, what are some quick fixes that you or I or someone else could do right now this year?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 21:14

I don’t think that there are any quick fixes, I think we need to take a broader look at how we do scheduling. Because of the way we schedule things. We ended up systematically excluding a group of students from computer science. And these are students who historically haven’t had opportunities to take computer science classes. So I think it’s a serious problem that we need to address.

Justin Reich 21:42

Our is super clear, we cannot change the schedules at this point. Sometimes imbalances will happen when you only offer one section of a course like we’re doing this year with intro to CS. We’re offering intro to CS during period five is super complicated. We’re offering intro to CS in period five are offering algebra and period five and period one. Anyone who has intro to CS for period five just is going to have to take algebra in pain one. What if I got you a teaching assistant to help with the class?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 22:16

I don’t think it’s super complicated. There are a few weeks left before school starts. We change kids schedules all the time. I don’t think a teaching system solves the underlying problem. Why can’t we look to changing when the math courses are scheduled so that all of our kids can have a chance to take computer science.

22:48

Thanks for coming in. I want

22:52

thanks for coming in.

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 22:54

So, hope you guys enjoyed that scenario. And appreciate you having Justin play the angry principal. I know that one of the things I find, even though I’ve done this scenario many, many times is every time I do it, I still feel that jolt of like, Oh, I’m talking to the principal. Like what’s he gonna think of me? Like, how can I make this argument? I think that that kind of shows the affordances of these types of simulations that even though just talking to a video, I know that the video isn’t gonna actually respond in the moment on a real person, I still feel that that emotion as I’m going to scenario, a lot of our simulations are like this, that even though they’re not necessarily capturing all the authentic, what it would be like in the moment, there’s something about it that makes it feel very authentic. And we found when we’ve done this with, with now 1000s of people People often say yes, it does feel authentic, it feels like something that would actually happen in real life. And that’s really a testament to all of the people who work to design these scenarios to be really impactful. So last spring, we launched the course course called becoming a more equitable educator, and we took these simulations, and we put them within within the course. So the way that the course was structured, is that within each unit, you would sort of be introduced to a topic, and then you would do a simulation about that topic.

And then after you did the simulation, you would watch a video of other teachers, we actually went to different schools around the country did the simulations to teacher and filmed the debrief of a debrief with them during the simulations that included interviews with individual people talking about the decisions that they made. So even though it was an online courses, obviously last March, like right when COVID was starting, so many people were sort of turning to online learning that time so even though it’s online, you’re able to see kind of what other people are thinking and doing in that moment. And the course itself was structured around this idea of educator mindsets. And we framed it around four pairs of mindsets. And the idea is that these are things mindsets that are out of balance in US schools. So just to give an example, one of the minds is that we looked at is equity versus equality. So equity is that sort of everyone gets the thing that they need. And if it’s some people need more things, they should get those things. And we should focus on individual again, not on giving everyone the same thing. Well, equality means that everyone gets the exact same thing.

And we shouldn’t give people special treatment. Now, what we argue is that it’s not that equity is good, and quality is bad. But the problem is that these mindsets are currently out of balance, that we have too much equality, and not enough equity in schools. And what we want to do is we want to shift people’s focus to thinking about as they make these decisions, how can I add more of an equity mindset. So in all of our views, and of course, each of them was framed around these pairs of mindsets. And there was a simulation that was attached to each of them. So this is all kind of a setup for the research that we ended up doing. So in the in the course there were 963 people who did at least one simulation, and there were four simulations. And of course, each of them that was embedded within one of the units. says it’s difficult to read the presentation. Can everyone see my slides? Do I need to make it bigger?

Justin Reich 26:49

I think if you can just if you don’t mind sharing the link.

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 26:53

Sure. Yeah, I’m happy to do that. You can? Yeah, I’m happy to do that. We are, I will put it in. Thank you for that feedback. I’m putting the link in the chat so people can take a look. Okay, thank you. Go back to the presentation. So as I was saying, we had four of these simulations embedded within the course each within one of the units. So we had a lot, a lot, a lot of text data, probably more text data than any person could look at qualitatively.

So I was interested in how can we use natural language processing tools to automate some of this analysis to understand what are people doing in these simulations. And so I looked into different ways of using natural language processing. There has been a lot of research about that has used natural language processing within large scale data sets. Just to give a few examples, they’ve used it to do automatic scoring of cognitive tasks or sort of machines wearing of assessments. People have used it to predict people’s affective states. So there’s one study that will that looked at what our students feelings about math, and they looked at people’s responses within a online math curriculum, and correlated that with student self efficacy for for math.

And then a study that Justin actually worked on was looking at our responses in discussion forums and trying to see, and this was a course, that was political course. So do conservatives and liberals, how do they engage with each other within discussion forums? So there’s a lot of different ways that you can use natural language processing to make sense of large data sets. And I was really interested in can we use these tools? With our simulation data? Can they provide us some information about what are people’s experiences within these simulations?

And the particular method I use is something called structural topic modeling. So a topic model is a model that detects underlying patterns within large datasets by identifying leading topics within within a text dataset. And what’s nice about topic modeling is it does not require any a priori assumptions about the structure of the data, so you don’t have to have labeled data in order to use topic modeling. It draws the topics from the data itself, so this was particularly good. We didn’t have any labeled data. So it was a particularly good for this test dataset. And we’re also interested in exploring what are people doing. Within within the simulations, we used a, what’s called a mixture model. So this is how the top of model works. It basically estimates a probability of a topic appearing within a text and a word appearing within a topic. And I’ll kind of give you a little illustration of how that process actually works. And the particular form of topic modeling that I use is allows you to include covariance that allow you to see associations between a topic appearing and some characteristic about a person. And I’m going to kind of dive into that a little bit later and show you how that worked within our analysis. So this is kind of the the pipeline for how structural topic modeling works.

So kind of the input is, is your text data. And in our case, it was sort of a big Excel file with each row was a different response within the simulation. So mostly simulations, you saw sort of three of the ones from Ross or justice, although simulations were basically kind of prompts and then people wrote in, wrote in or said their answers, and we automatically transcribe those answers. So you kind of have this big, you know, basically soulfire data. As soon as you take that data, the first thing you do is you have to process that data. And this is important, because within those pieces of data, there’s a lot of words that are not that informative. So things conjugations like and or prepositions, pronouns, like all those don’t really provide you a lot of information about what’s happening in the tax. So the sort of general exception rule is to kind of pull those out of the of the text that you’re looking at. Another thing we did was stemming, which is to say like, getting rid of all of the conjugations.

So like, you know, for example, explored, we explorers, exploring explored exploration, we took off, it took all those and kind of made them one single word. So that way it focuses on the content and not on the particular way that’s used within a sentence. Another thing that we did is we separated out by line. So I was interested in topics appear with individual responses, and I thought that there might be multiple topics. And so a way to kind of pinpoint when a topic is occurring, is by separating that into individual lines. And this kind of ended up giving us you know, even more rows of data to look at. And finally, under the recommendation, from the authors of the of the structural toggle model, I removed infrequent words and words, it didn’t appear that frequently within each document, check them out, we ended up still with, you know, over 1000 different words for them, each simulation, and kind of what you end up with is this document term matrix. So it’s basically like, think of like a big Excel file. And each column is a word. And each row is a different piece of tax, or what’s called in the, in the national image processing world documents. So basically, if a word appears in the document, it’s a curious one. And if it’s if, if it doesn’t go to zero, and this is for every single document in the tax, and what the structural topic modeling does is it takes that really big matrix, and it kind of looks for correlations between words within documents and documents that are have the same word. And it kind of spits out a set of topics that have certain words that are associated with them, and and documents that have certain topics that are associated with them. The challenge is that you have to specify in advance how many topics you want. So if the type of model will spit out 60 topics, it will spit out five topics, you’d have to figure out, kind of using some metrics, how many topics do you actually want the model to produce? And there’s a number of different ways that you can do that to kind of figure out what is the right number of topics to extract. The larger issue is that the topics don’t come pre labeled. So it’s not like it spits it out and says this topic is about, you know, baseball, like you have to assign those labels yourself. Now, sometimes it’s more obvious, and sometimes it’s less obvious. Those of you if you’re familiar with factor analysis, or cluster analysis, the same issue with the model will kind of group your data, but then you have to as the researcher to figure out what does this data actually mean? So I’m gonna walk you through example of how we kind of came up with labels, and this will sort of try to show you how the topic model works. So these were two topics that appeared in

35:00

The model that I ran for Jeremy’s Journal. So one of them is topic seven. And in this graph the purple.is the probability of it appearing within topic. Topic seven and the is actually reverse, but the the green.is, the probability of appearing in topic 10. And so I was interested in this graph that illustrates both the probability of a word appearing in topic seven, and then the probability of it appearing in the other topic, you can see that certain words are more likely to appear within one topic, and less likely to appear in other within another topic. So, for topic seven, the words today, yesterday better feel are very likely to occur within that topic. Well, for topic 10, Doctor, absence, note, mom, those ones are more likely to appear. So, this is kind of giving us some sense of like, what is actually going on in that topic. So, now, I’m going to give you a phrase and you’re going to have to, I want you in the chat, to say which topic Do you think that this piece of text come from? is it from? topic seven, or topic? 10? So, just a reminder, this is the this is the words for topic seven. And these are the words for topic 10. So, I want to look at this. And just sort of this, do you think it’s a topic seven or a topic 10?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 36:37

Go back to the Okay, I see a lot of sevens. And you’re right, the model agreed with you, and said there was a 75% probability of this, this, this piece of text containing topic seven. Now, let’s try this one. Remember, the school’s policy is that you need to sign doctor’s note in order to be excused from class. So this is topic seven, or topic 10. Just right in the chat, seeing a lot of 10s. And again, you guys are right. This training Exactly. There was a 60 models and there are 65% probability of topping 10 a pyramid. I should say not all of the topics for this clearly delineated between two sometimes it’s a little more ambiguous what exactly the model is detecting.

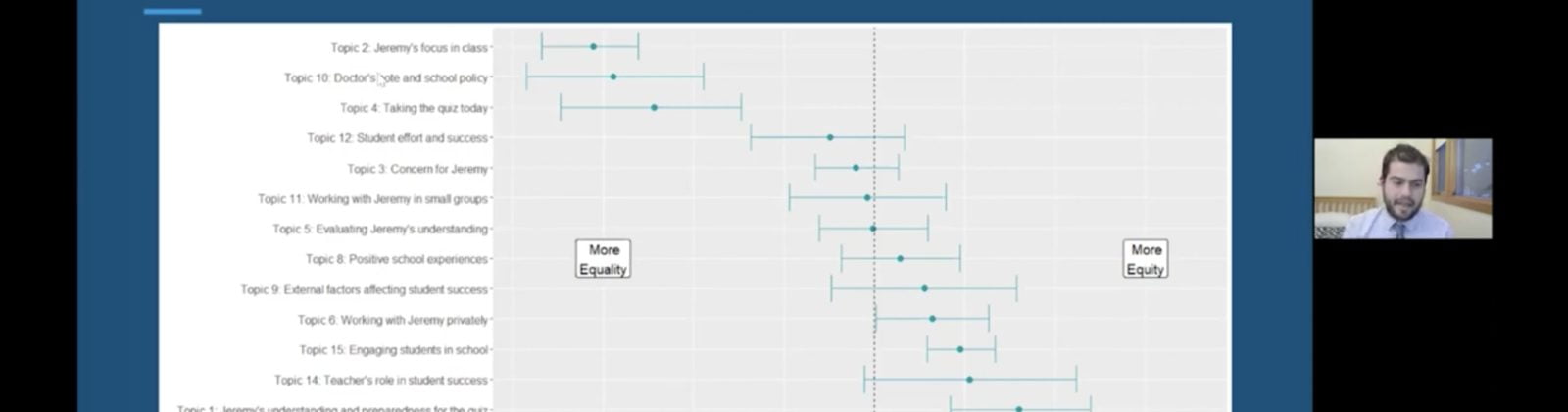

But we what we did is some kind of similar to this process, where we looked at what documents the model said was likely to that topic was likely to appear in and the words that were heavily associated with that topic. And kind of through that process, me and some other graduates, research assistants, graduate students, we came up with topics. For topic seven, we they will back glad Jeremy is feeling better. And for topic 10. We labeled a doctor’s note and school policy. And we did this for all the topics that were extracted, and all this all of the simulations. So once we extracted the topics, what we were interested in was, are these topics associated with anything? Do they? Are they associated with participants attitudes toward equity. And remember, I said earlier that the structural topic model allows you to include predictors. So in this case, we want to know, was there a relationship between what participants said on surveys in terms of their attitudes toward equity, and we had surveys for each of the mindsets in in the course there was a survey for equity and equality, there’s a certain rate for difference in asset. And we wanted to see, is there a association between how I responded to a survey and what topics I noticed within the simulations. And what was really exciting for us was that there was a pretty strong connection that certain topics, you are more likely to notice if you had reported on a survey more of an equality mindset. And there were certain topics that you were more likely to notice in your equity mindset. So what’s interesting is that the doctors know people who mentioned the doctors no are much more likely to have an equality mindset.

Well, people who ask Jeremy how they were feeling were much more likely to mention service. They had equity mindset. We found this in all the simulations that we did that there was association to what topics you noticed, and your your your mindsets on surveys. So this was exciting for us to think about, like our simulations, acquisition nations actually measuring something real about what people think and believe having to do with equity but That’s sort of good for like a measurement piece. But people Justin and Peter were in question was interested in? Did these courses actually work? like did you actually change their mindsets over time? So I wanted to look at is there a way that we could use these simulations to understand are people actually changing in their mindsets over time? The problem is that we had four different simulations.

So you can’t compare the topics from one simulation to the next because they were totally different simulations and totally different subjects. So the topics are not necessarily comparable. But what we could do is we could compare you to a set group of people. So what we did is for each, for each simulation, I calculated the maximum probability that any topic would appear in your responses. So you kind of end up with a with a a table like this. So for each topic, each row is an individual user, and there’s a probability that that topic would appear in any of their users responses for that simulation. And so this is not real data. But you can this is sort of what it looks like, when some people were more likely to mention one topic, some people were more likely to mention other topics. And then I was interested, okay, so we have all that data. Um, let’s compare them to the people who started the course with the highest equity beliefs on the service. So I took the top core trial, top 25% of people on on their pre survey in terms of their, their educator mindset, beliefs, and were they more shifted toward equity or equality or asset versus deficit? So I wanted to see like, do other people in the course do they become more similar in the topics that they’re mentioning and simulations to those group of high equity users? And so I’m going to show you example, from our first simulation, I want to go back and explain something. So how do you see how similar people’s topics are to each other? Well use this concept called Euclidean distance. So those of you who remember

42:13

trigonometry, you know, v squared, if you know the staggering theorem. So this is basically like, what is the distance to one point and any other points? And it basically took each person’s topics and looked at, okay, how similar is my responses to this other person’s responses, and the closer my responses were on to their responses, the more similar, I would say that my responses are. And so you can see in this example, like, if these are like the top reference to this person’s responses is closer to this person’s responses. So this is just not the what the data really looks like. It’s actually not two dimensions. It’s many, many, many dimensions. But this is sort of basic idea what we’re talking about, we’re talking about distance. So in Jeremy’s Journal, the people in the fourth, the first four tile, so with the lowest equity beliefs, were the furthest away from that reference group. So their responses were the least like that top 25% reference group. And this percentages here, it represents sort of, on average, for any topic, how far percentage wise, my response was.

So it’s not a huge number. It’s not like, you know, 30% 60% versus 30%. But on average is about a 4% difference in any type of between someone in the highest group, and then someone who started in the lowest category. And so essentially, this is the first simulation, how do people change over the four simulations in the course. And so it was really exciting for us is that in the first simulation, you see that one, these other people in the first, second, third, fourth quarter, while they’re all kind of further away from the people in the fourth quarter, and as they progress through the course, they all get closer, both to each other, and to the fourth floor tile.

So I think what this is showing is that people are becoming more similar over successive simulations. And in this data, I’m only looking at people who did all four simulations in the course. So it’s not that, you know, people are dropping off and the last equitable, people are leaving, basically, we’re actually seeing people are changing to become more similar to people in that forest for tile over the course of the course. So just to summarize, on natural language processing tools, such as structural topic modeling, can help with these large simulation datasets to understand what’s happening in the simulations and to identify topics that are emerging.

And what was really exciting for us was are we would kind of bring these results to our designers and they’ll say Yeah, actually included that that thing and that’s really On purpose, I want to see how people respond. So it’s interesting that the that the machine learning model was actually able to pick up on some of those nuances. The second thing is that what you notice when people notice and mentioned the simulation was associated with their beliefs or attitudes. So suggesting that simulation is capturing differences between people, and how to respond to different types of situations. And finally, that interesting way of evaluating learnings that we can see by comparing simulations over time, we can see how people change in terms of their beliefs, and did they become and becoming more similar converging with one another as the course progressed.

I know we’re running short on time, I just wanted to briefly talk about two future directions. One is that we’re going we put in a grant to do a study where we’re actually going to be doing this with teachers in grades three through eight in five different districts across country. So though our moves have a lot of educators, usually just people who kind of randomly come into the course or hear about it. So in this one, we’re actually going to go out and recruit people, and we’re going to be able to link it to data about their students. So we’re interested to know, does your response in a simulation is that actually predictive of student outcomes? And because right now, we don’t really know whether these these behaviors are actually predictive of anything outside the simulation. So we’re hoping with the state to actually understand a little bit more about how his behavior in the simulation connected to behavior outside the simulation, ultimately, how does this affect students experiences. Um, and then this other thing I’m really excited about is this idea of being able to give automated formative assessment and feedback within the simulation. So I’m gonna play a short clip of what Roxanne Josh roster justice could look like in the future. So this is like from the last prompt that you heard.

Justin Reich 46:57

Anyone who has intro to CS for period five just is going to have to take algebra in paint one, what if I got you a teaching assistant to help with the class?

47:07

So now I’m writing? That does sound super complicated? Yes, a teaching assistant would be great. So I’m submitting it and then saying pops out. He says, Remember that your main concern is the imbalance of classes, does a teaching assistant solve that problem? So this is actually feedback that someone a facilitator we give in person. So we’re we’re hoping to use machine learning models to actually be able to detect, like, what are people saying, Yeah, teaching the system would be great to be able to give them that automated feedback. That’s something Marvez actually has been doing a lot of work on over the past few weeks. So I’m hoping that this is something that we could actually implement in the near future. So So thanks, again, for listening to my talk. I’m glad I was able to come and talk to you. And I’m really excited to hear your questions. And to hear kind of what what you think about all this?

Vivek Bald 48:18

You know, open it up to questions, questions. I have one myself. I guess I wanted to get a sense of wasn’t quite clear on when you showed the simulation the first time. Yeah. How how that works, in terms of how it’s been? How the simulation has been built to respond to verbal responses, is it? And what responses like pre recorded responses from the principal? You know, what is the spectrum of responses from the principal that that are going to be potentially chosen, you know, algorithmically to respond to various responses or various inputs from the person who’s going through the simulation?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 49:34

Yeah, that makes sense. That’s a really great question. Question. The short answer is that it doesn’t now like there’s no algorithm, no matter what you say, Justin will give the same response in that simulation. I think there’s actually two things. One is that we had it when we built this we had sort of started to develop the technology to be able to respond In real time to have more responsive video. But the other thing is that often if you’re having an argument with someone, like what you say that, that you’re actually not talking to each other, you’re actually like having a conversation where like you say something the other person just sort of ignores what you’re saying. So we’ve actually found with the the argument types of simulations, that it actually works pretty well to have somebody have a conversation with someone who totally ignores what they’re saying. And the person who designed this also was really knowledgeable about schools and how these conversations works. And so when she was designing, I think she she really thought about, like, the types of things that our principals would say in that moment.

Vivek Bald 50:47

I was actually going to say that the the lack of varied responses from the principal is probably closer to reality than if you tried to create Apple responses.

50:58

Yeah.

Vivek Bald 51:06

I haven’t the questions, but I want to make open the floor to everyone. Well, I have my next question, which is just related to the the future directions that you just spoke about? And you were talking about the potential testing in the field? Where I just remember the the number 252? I don’t know, I don’t remember if that’s 252. Teachers or schools?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 52:04

Teachers, teachers. Right.

Vivek Bald 52:06

Okay. And so I guess the question that I have there is, if they are self selecting, to take part in the simulations, is it you know, how are you correcting for the possibility that those teachers who were open to, to going through these simulated simulations that are geared towards, you know, shaping or geared towards guiding people towards a more equity based mind? mindset? That, would that be a self selecting set of teachers who would already be sort of a closer to that mindset or be more willing and open to have their mindset changed through a process like this? If that makes sense?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 53:09

Yeah. So I actually think what you’re pointing out is a good observation about the the course beyond the course that we did. Because, you know, we, the courses is sort of open and free, and you can take it, but the types of people who take the types of people who already care about equity issue equity issues. So one of the challenges kind of right up front is that there wasn’t a lot, there wasn’t as much variation in the types of responses as we would have liked. So like, even those, I would say, like, you know, I said, the low equity, the first floor tile, but that first word, while probably most schools would actually be probably like some of the more equitable educators, but within that school, the people who are probably like the most in need of the course, and probably the least likely to be taking it, I think, and one of the things that we want to do with that study that I was proposing is, is do more active recruitment of teachers. So we’re going to be working with districts to sort of identify schools, to participants, they will actually be like, recruiting teachers and paying them money to participate in this course. And so I think what we’re hoping is that we’ll get a broader and more diverse group of teachers then the types of teachers that we got in took the move, and hopefully we’ll be able to reach teachers who wouldn’t necessarily like pursuing an online course but equity on their own.

Vivek Bald 54:43

roya and then Tomas was that and

Roya Moussapour 54:49

I was curious, I’m sorry, I’m outside. So if you can’t hear me, that’s why I know that something we thought about a lot that I work lab is sorry. How we transition a shift in mindset to a shift in practice. And I would love to hear kind of your, your thoughts on that in terms of this work. And where you see that going with kind of the implementation teachers?

55:15

Yeah, I think it’s, it’s a, it’s a measurement challenge, especially in a MOOC because, you know, we get, we don’t know in advance who was going to take our course and they kind of show up. And, you know, it’s not like we can, like, be like, okay, we’re gonna go to your class on this day, we actually were planning at one point, sunset, and Chris Buttimer aren’t the postdoc who worked on this project, we had a whole plan last March that he was going to, like, find schools and contact them and travel all around the country to do observations. But then obviously, COVID happened. So that’s not that that kind of was not no longer a possibility. But I think that it will be like, I’m really excited about the work that you’re talking about. In Spider Man, I think it’d be really interesting to actually see kind of what, what what our teacher like, if someone does something a simulation, is that related at all, to to their actual practice? And is there is there a correlation there. I suspect that that there is based on like, what we’ve seen in terms of, like survey responses, but it’d be interesting to kind of actually connect that to actual practice.

56:36

Tomas?

56:38

Um,

Tomás Guarna 56:39

my question was really similar to us. But I think maybe I can maybe frame it in a different way. Um, so yeah, first of all, thank you for the great presentation will consume really interesting, and I’m really excited to what can be done with this methodology. So this would assume from the assumption that there is a goal to increase an equity mindset, right. And I was wondering, I mean, this is something that I can probably get behind out and behind. But I wonder if, if there are other possibilities to do this, like with other values, other normalcy values that, that maybe are sourced from teachers, and maybe like, not from academic labs, but to see what, what the other tier swopped say about that? And I was also wondering if, um, yeah, so I think this is pretty much what you just answered. Right. But I guess the what will be the conclusion from from from this method is that you can tell people that certain certain, yeah, actions are associated with a certain mindset. But I wonder what’s like the extra step. Right. Like, and I guess that’s what you addressing the MOOC. So I was wondering if we could discuss what are the contents of that work? Yeah.

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 57:55

Let me know if I understand your question, right. He asked him, like, you know, what is like, okay, we can measure these things. But how is this actually going to change people’s practice? That kind of stuff? So

Tomás Guarna 58:07

the first one is whether you could like timing, other normative values, instead of equity forgetting, like, you know, if they want to make more solidarity teachers, like, what does that mean? Then? The second question would be to, if you could talk about the MOOC experience, like how can you turn this insights in that data into into specific practices?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 58:24

Yeah. So I think the first thing is that we have done so equity is sort of one area that we’ve worked on, we’ve done it in a number of other areas, including roya, has, has done a lot of work on on math instruction, which is less, it’s less a question of, and where you could disagree with anything that’s wrong. It’s more of a sort of teaching certain skill sets, then a kind of normative value, although there probably our mortgage values that are baked into those particular skills that we’re trying to teach. We also marvez and I worked on course, called civic online reasoning, which was about preparing teachers to teach students how to identify misinformation online. So it’s based on a method developed by a group at Stanford, called basically to call lateral reading where you you if you see something online, instead of like spending a long time reading through it, and trying to determine is this real is this not real, which is sort of the traditional way that teachers have been taught to how to teach information literacy, they say that the best thing to do is actually Google at Google and see, like, who is behind the information. Another important thing in that that course is that many teachers and many of you probably experienced this, like think that Wikipedia is bad, like basically that Wikipedia is totally unreliable as a source. But you know, that actually, you know, there are some issues Wikipedia, but it can be really reliable, especially for finding sort of basic information about something and Wikipedia. also cites a lot of sources. So you can go to those sources and look up the information. So that we actually developed practice space as practice based simulations to, to, like, have people kind of do these exercises to see how much they’ve learned about that particular skill set. And marvez has as hopeless as you can plug in your weapon, they’ve done this really cool classifier that basically detects like, if response to one of these tasks and say like, Okay, did you figure out that this tweet was from a parody account, or, or not? And we’re hoping to use those to give people feedback on learning. I think ultimately, so like, answered to your second question. So we have some data from our course. And it’s all self reported. So, you know, take it whatever things you thought you need to that people up to over the course. We’re more likely after the course in particularly four months afterwards to discuss equity issues in their schools and to participate in networks around equity. So there’s some evidence that the course African people are more likely to engage in actions around equity, and learning and I would really be interested in learning more about like, what does that actually look like? And is there a relationship between taking the course and doing these things? That’s actually one of the reasons why we’re proposing this study is to do a randomized experiment where we assign randomly assigned teachers who take the course and we see this actually change their behavior. So I think it’s definitely something that I’m really interested in as research and also interested in like canned stuff, like a online virtual course, and that actually affect behavior in the real world. Thank you.

Vivek Bald 1:02:03

Ambar, and then there’s the question in the q&a from will.

Ámbar Reyes 1:02:11

Thank you, thank you be back. And you’re sure. I was wondering, so when you may, like when you ask us, like, which option would we choose? We all chose one, right? In like, like, that relates to equity. But I’m just wondering, like, even though, like, if teachers answer, one, and they are more likely to think about equity, also, I guess, like the school rules, effect, right. So I was wondering if you have thought about actually making simulation to change the way the principal thinks about it, rather than the, like the professor, because they could, you know, like, they go about liquidity. But, you know, like, the rules as a rule, so I’m,

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:03:05

yeah, yeah. And I think that’s a really great point. And something that, you know, comes up a lot in the course is that, you know, we intentionally framed the course, around these sort of individual moments and teaching. And the reason we did that is probably because those are the easiest to change. So like, I, as an individual teacher, I can like make the choice to, like, interact with the student differently, or push for something or like, bring something out with my colleagues, it’s more difficult to sort of more systemic issues. I think our theory of change is that like, if people start to notice these things in their practice, and they start to talk about other people, that kind of builds up the momentum to sort of change some of these bigger things. So like, you know, an individual person saying, like, hey, actually, like, let’s think about how our schools policy about the document on how does that affect, you know, students who may not have health insurance or may not be able to easily get to a doctor may not have the transportation, like, how does this policy affecting those particular students? So I feel like we start with sort of the individual and that can kind of lead to some more systemic changes.

Vivek Bald 1:04:22

Great, there’s Will’s question. And then Emily added on to to that question. So I’m going to read these so others can can hear them, but feel free to follow along in the in the chat bar. So we’ll writes I’m interested in the notion of discretionary spaces in classrooms, and the types of situations in which they arise. I’m curious about how you go about deciding which specific types of discretionary spaces slash scenarios to focus on in the simulations that you develop for the courses and then Emily adds, it’s also interesting to think about whether or not teachers understand them as discretionary or not, in particular contexts, and would interact with changes in their interest in enforcing school rules, which Yeah, so

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:05:18

yeah. So all these scenarios are developed, based on Twitter, real things that have happened in schools all the time. I know my wife is is an educator, and she’s always like the I’m always like, okay, here’s an example that you just did. I think it’s perfect one for a teacher moments. And so I think kind of like the characteristics of good, like discretionary spaces, one word that this The answer is an obvious I think the one I gave you actually was a little bit more obvious than, like, really good will be, but like, has some sort of tension between like, do I want to do this thing or that was if it was an obvious decision that everyone would would just do that. But there has to be something kind of countervailing that would make you think, well, maybe I don’t want to do that. I’m one of the things at the end of the of the Jeremy’s journal simulation is that he asked because he’s missed school. And because, you know, he asked if he can, if he can be excused from taking a quiz that you give every week. And so he comes up to you, it’s like, kind of get out of squares.

And whenever we’ve done this, we’ve gotten many, many different responses, and there isn’t really a right answer. So like, if you give him the quiz, you’re like, not equitable. And if you don’t give me the picture equitable or vice versa, because there’s, you know, reasons for wanting to give him the quiz. I think what’s important is like your reasoning behind it, so maybe we’ll say like, Oh, I’m giving him the quiz, because I want to know how he’s doing. And then I’ll give him feedback. And we’ll talk about and I’ll understand more about, like, what is going on with him, versus someone who’s saying, Oh, I don’t want him to give him the quiz, because like, everyone else has to take the quiz. And that’s just the rule. And he’s got to adjust. This is the real world, like, no one’s gonna care about his situation. So like, the decision is not as important as the reasoning behind it. And that’s actually why I think that the natural language processing is so important. Because we could just construct in scenarios, it’s like multiple choice, like, do this or do that. But it doesn’t kind of tell you like, why, like, why did you want to do this? And that’s where I think some of the text analysis stuff really comes into play. The last is to understand the nuances of why people pick something and not the other thing.

1:07:37

Purpose.

1:07:40

A great presentation, Josh?

Emily Grandjean 1:07:43

Well, I just was wondering if you could go into a little bit more about, like, the development of the scenarios, like who are the designers and like how we plan for research, especially in the context of IAS where we’re going to be doing it over all these districts with all these different teachers in different contexts?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:08:01

Yeah, I’m just saying like, how do you how do you decide to work with different types of audiences? Um, yeah, I mean, I think like, one of the the challenges, especially in a MOOC is that you’re doing it for a global audience. So you’re doing it for people who are, who are, like, may not be as familiar with certain things in the US contacts, I think what works well as video is like, the universal enough experience that many like people could identify with it. So even if the specifics are not the same, I know this is actually something where I thought like, originally, like, oh, people aren’t going to get this Jeremy startle scenario, because it’s so like, specific to like, US schools. But when I actually looked at data people a lot of people got it really understood what was happening there. Even if they don’t understand it, manipulate the specific details are important. And that’s, that’s why I think that the like, the characters and their artwork is really where and I guess it’s kind of connected to the media piece like this is what makes the scenario meaningful via possible experiences, if you can kind of connect to what’s actually happening in the in this situation.

Vivek Bald 1:09:18

I have another question. That’s, that is more I guess, geared towards you’re taking this opportunity to talk about methodology, since half of our students are are taking a media research methodologies class with me at the moment. So I wanted to just ask you about the research design and sort of iterative design based research. Specifically in relation to the natural language processing How? How you’ve built that out? You know, what, what are the steps when you’re when you’re building that? What are the steps that you go through? In order to fine tune? how that works?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:10:19

Yeah, um, so it was a very iterative process, I would say, it wasn’t something where I was like, I know exactly what I want to do, like from the beginning. I had, like, we had been doing these scenarios for some some time before we did the course. And so I had some understanding of like, what the universe of possible responses were to these types of scenarios. So I knew that like, there were certain patterns to like, what people how people would respond. And like, there were kind of like, you could kind of like, see, like, oh, people responding this way, or they’re on this way. But all that data, you know, was sort of like a small sample. So I didn’t actually know exactly how it would work, how it would work, when we kind of did it a larger scale, from the other sort of, like decision that I had to make.

I hope this isn’t getting too into the weeds is like, thinking about the goal with using the natural language processing facility, one approach could have been to say, like, Okay, I’m gonna, like, score each of these responses and like, see if I can build a kind of classifier to predict, like, what are people or people, you know, acting equitably or not accurately? But I don’t want it to leave it open ended to feel like, I’m not gonna, like predetermine what is equitable, and what is not equitable. I want to see like, based on the data, like, what are people? What are people noticing and aware of differences between people and what they notice. So that’s kind of the like, framework I use, and why here I was sort of leaning toward more unsupervised models that would allow kind of lab data to sort of like, generate, and then once they had it, then that was a kind of, like, as I was saying, like, labeling is not always is a kind of a difficult process, because you can kind of get to make a subjective decision about what the data means. And that’s where I actually did a lot of conversations with the people who designed the simulations, looking at the data talking with other people getting some kind of validation by thinking about like, Okay, do other people see the same things that I’m seeing, because it is a it’s subjective, but you want it to sort of be like transferable, so other people could kind of come to a similar conclusion. And then that’s one of the challenges with this type of analysis is that there is some, like, researcher subjectivity, and you don’t want to sort of hide that behind the like, objectivity of like, these are the numbers, you want to say like, this is the process that I use to kind of come to this this conclusion. But actually, we actually did actually had people like, who weren’t involved at all in the design of the model, like I gave them like, a task where they had to choose which topics kind of like what we did this exercise, like, I like selected a piece of text, and then like, gave them a bunch of different topics. And one of them was the one that the model said was most associated with. And so we actually could predict, like, had them say that, themselves are basically doing what the model is, like, you know, which topic is most associated with this piece of tax, and then it actually was match the model best 65% of the time. So it wasn’t like a perfect connection. And often, it was in cases where the model was kind of iffy about, like, what what was actually in the tax. So I think it’s like one of those cases where like, the more like cases where it’s more clear, kind of is easier for people to kind of correspond with the with the model, in cases where it was less clear that there was more ambiguity there. Just a

Vivek Bald 1:14:03

quick follow up is, you know, you touched on just now, the, our particular response, you know, might be, I think you were using the example of whether or not to give the student The, the, the test and how they’re, you know, one, two teachers who decide to give the student that test might have different reasoning, one of which is more aligned with equitable mindset and one is not

1:14:40

to

Vivek Bald 1:14:42

and maybe this is partly, you know, already answered, but I’m curious about how that kind of qualitative assessment is built into the overall project. You know, whether You know, so that you can since like, you’re saying you’re not pre determining in the model, which, which kind of response corresponds to equitable mindset and which is not. And so that in the those those kind of like fine areas or gray areas? Yeah, it seems like more qualitative engagement with the subjects, or with the teachers is sort of what will give you the data that you need. And so I’m curious how, you know, the kind of interplay between that kind of qualitative method, and the kind of modeling that you’re doing? Yeah.

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:15:40

Yeah, I mean, I think I see, like, Justin’s comment about, like, using unsupervised approaches to compliment traditional qualitative bottineau grounded theory, types of analysis. And I think that’s actually a good analogy for, like, how do we, you know, look at this type of data, because, you know, in the course, was probably, you know, over 100,000 rows of data. So, now, we could have coded all that data, but I probably started working on it now. And what was really interesting was like, once you see once you kind of can see what’s happening in the data, then you can sort of start to put on some of your, your qualitative lens, and kind of do some more looking at like, what does this actually mean? I was sort of my training is quantitative, but also done some mixed method, qualitative research. And I’m, I’m sort of interested in kind of that that space of like, how can we use like large data numbers, but also kind of understand like, you know, more qualitatively what, what are people thinking? And how is it you know, that you cannot actually is more difficult to capture with like, multiple choice like serving? So this is why like, I’m very excited about this type of methodology for Thank you.

1:17:08

Other questions?

1:17:16

Okay.

Vivek Bald 1:17:20

Well, we can, we’re almost at at 630.

Justin Reich 1:17:27

I have one last suggestion. This is Justin, sorry,

1:17:30

my house is chaos. So I’m not gonna say okay,

Vivek Bald 1:17:33

that’s okay, the students got a bit of a taste of the chaos in my, in my house that the end of the last session. So

Justin Reich 1:17:40

if we have just a couple of minutes, if folks have any sort of either substantive or stylistic suggestions for Josh, thinking forward to head to his next presentation, if there are parts of the presentation, where he lost you, or became an interesting or problematic, or even parts that like really connected with you and engage you, I’m sure any of that feedback, do you think Yeah, you know, in your that you’ve seen lots of these kinds of talks, too. So if there are thoughts that you had, I think that would be really,

1:18:07

really welcome and valuable.

Tomás Guarna 1:18:09

Who’s gonna be your audience?

1:18:11

Sorry,

Tomás Guarna 1:18:12

who’s gonna be your audience for your talk?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:18:15

So this is it’s a at Northeastern, it’s the, it’s their College of Art and media design, and also Applied Psychology. So they’re new people who are more sort of like Media Design, folks. And they’re also new people who are more kind of like working in schools, as educational psychologists. And so it’s sort of, actually I think this is a good representation of the diversities of the people who are like, you know, may not know that much about education, but know a lot about design and people who know a lot about education, but might not know that much about design. They’re also part of, and that’s why I spent actually more time than I would normally is they’re interested in someone to teach statistical methods. And so I want to also showcase some of my own ability to explain just all concepts in in a more lay audience type of way.

Tomás Guarna 1:19:11

From the standpoint of someone like who was like, definitely on the media and arts, nice things that don’t have numbers. I guess they at some point, you lost me with the technical stuff. But so I would consider framing it like, more, more look at the story that you’re telling. And not just start from the methods. Good. Maybe?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:19:34

Yeah, that’s helpful. Yeah.

Ámbar Reyes 1:19:40

Something that was difficult for me was when you were asking us like to choose between seven and 10. Yes, because I couldn’t like see, you know, like, I couldn’t. Yeah, the other one, so yeah,

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:19:53

yeah. Yeah, that’s, yeah, I thought about that. It might be good to have like the visual there. Obviously, you See the word? distribution? Right? Yeah.

Vivek Bald 1:20:09

I guess one, one thing and this was behind, I think one of the questions that I asked was, I was the first time when you were going through the simulation with the, the video responses from, from Justin, it wasn’t, you might want to do a bit more contextualizing there in terms of what the user experience is. Yeah. And in part, I think it was, I was hearing I was hearing your voice in audio, right. But it wasn’t in real time.

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:20:45

Yeah. Okay. So

Vivek Bald 1:20:46

then I got confused about like, what, for a person who’s actually going through that simulation, what are they inputting? And how? Yeah, and then how are they experiencing the response?

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:20:57

Yeah. What’s the point? Yeah, I actually thought about that, as people thinking, talking in real time. Was it helpful to have that example? Like, do you think that is helpful? Should it be shorter?

Vivek Bald 1:21:16

I appreciated that example.

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:21:19

Yeah.

Vivek Bald 1:21:20

Because in part because of, you know, showing showing people what the actual experience is going to look like for the teachers who are going through this simulation. And that’s why, you know, kind of fine tuning that so that it’s, it’s clearer what what that experience is, I think would be would make it that much more effective.

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:21:46

Yeah, that’s, that’s really helpful. Yeah, I can definitely, I think I can do that.

Emily Grandjean 1:21:52

Um, just as a point of clarity, I was wanting to make sure I understood properly that people can respond however way they want when they’re in the simulation. And those two examples he gave us the beginning, were just, like, common examples that represent Yeah,

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:22:07

yeah. Yeah, I think that that Yeah, that’s true. So there’s sort of like, these were two responses that people gave, and like, kind of give options. Um, I couldn’t have it actually be like, open ended. I just wanted to sort of get the sense of like, the the binary. But I could probably make that clear that these were like, examples that people gave, and then it’s not like in the simulation, you have to choose between these two.

1:22:33

Yeah.

Emily Grandjean 1:22:35

Then to the documents that you’re feeding into your model

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:22:37

would be Yeah, yeah, exactly. But, yeah, I think I think that I could make that click that point a little bit

Roya Moussapour 1:22:46

clearer, clearer.

Emily Grandjean 1:22:51

Then now that I understand just to follow up on that, one question I had was whether, after getting these results, you sort of looked into some of the responses themselves to see whether the kind of I think convergence, you were showing with like a meaningful convergence, or whether people might be using the same kinds of words, but in different ways based on

Joshua Littenberg-Tobias 1:23:13

Yeah, maybe? That’s a good question. That’s actually not something that we’ve done. thought about it, but I haven’t actually kind of like, done more, I think he was sort of needs to do a kind of qualitative analysis to actually like, look at like an individual person. Um, I think that that, like, is very possible that it is people are picking up like terminology in the course. And then using it in the simulation, which is not a bad thing. Like it’s, I think that’s actually kind of what we want is that people just sort of like, learn things and then apply it. But I think, I think and I hope to come off and say that, I’m not saying that now. They are like becoming more equitable. And now they’re an act within the course here, like, you know, doing all of the equity practices. I think this is a longer term process. And then what we’re showing is that people within the simulated concepts are being more cognizant of the type of issues that someone with already a high equity mindset would see in that type of system simulation. Great.

Vivek Bald 1:24:26

Thank you so much. And yeah, in order to not repeat, last, last week’s explosion of my daughter into from the background. I will thank you and and thank everyone who joined us tonight and thank you all for your questions and your feedback. And Break a leg. Well, I don’t think literally Break a leg but

1:24:55

please feel free to get in touch with me. My email is jltobias@mit.edu. Any feedback is very welcome.

Vivek Bald 1:25:05

Thank you