Summary

(By Jason Martin Lipshin, CMS ‘14)

In the first Communications Forum of the year, former staffers of The Boston Phoenix, the city’s storied alt-weekly, gathered six months after the publication shut down to discuss its legacy and its role in Boston’s intellectual and cultural life.

“I don’t want this to be a funeral,” said Carly Carioli, who started working for the publication in the mid-1990’s as an intern and eventually worked his way up to be The Phoenix’s final editor. But nostalgia and eulogizing seemed all but inevitable, as both panelists and audience members affiliated with The Phoenix from over the years recalled its glory days.

Seth Mnookin, associate-director of the Communications Forum and an assistant professor in MIT’s Comparative Media Studies/Writing program, began by asking the panelists what made The Phoenix different from more mainstream publications like The Boston Globe. Charlie Pierce, a political blogger for Esquire and a staff writer at grantland.com, who worked at The Phoenix from 1978 to 1983, offered a response that was part history lesson and part anecdote.

“The Phoenix was part of the first generation to come out of the long form, narrative non-fiction of New York [Magazine] in the 1960s…We covered almost everything The Globe covered, but we did it with voice, we did it at length, and we did it with attitude,” he said.

Pierce went on to explain how many Phoenix stories had their roots in counterculture of the 1960s. In one revealing anecdote, he recalled reporting on a legal battle over the last porn house in Chelsea, in which he visited the theater and watched an X-rated film along with two jurors and a seventy year-old judge.

The novelist and essayist Anita Diamant, who started at The Phoenix as an assistant to the editor in the late 1970s, talked about how she went from answering phones and filing paperwork—which was, she said, “how most women got into the newsroom at that time”—to writing her own, first-person column.

“It was like journalism finishing school,” said Diamant. “I had the opportunity to really rethink the women’s pages…everything from women’s health to fashion to the way women were discussed in the media…I’d take stories that the women’s movement and feminism had identified and elevate them into something that was well-reported.”

Inevitably, much of the discussion focused around The Phoenix’s much-celebrated arts and cultural coverage. Poet and classical music critic Lloyd Schwartz, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1994 for his Phoenix work, pointed to the unique way the paper mixed high and low culture.

“Current rock music was always the center and got the most attention in The Phoenix arts section,” Schwartz said. “But there was always room, there was always the desire to cover the high culture.” Small, unknown operas might not have the same mass appeal as a piece about the first Sex Pistols’s show in America – an event which, Carioli pointed out, The Phoenix covered – but Schwartz said the paper’s editors always made room for both.

For Schwartz, the freedom to write honestly, without worrying about offending powerful players on the city’s arts scene, was another thing that made the paper a special place to work. “[It seemed that] there was a kind of pressure from the higher-ups at The Globe … you had to be very careful about what you said about the major institutions. But this was not the case at The Phoenix,” said Schwartz. “There, it was important to say that the emperor had no clothes.”

The panelists agreed that The Phoenix retained much of this un-intimidated, outsider’s attitude even in its last days. Carioli cited Maddy Myers’ work in feminist video game criticism and Chris Faraone’s coverage of the Occupy movement as examples of journalism one cannot find in the major newspapers.

Mnookin, picking up on a column by former Phoenix media critic Dan Kennedy, asked whether the paper’s demise was representative of the sheering off of some of the city’s rougher edges: With head shops and used-record stores being replaced by Starbucks and Pinkberrys, were there still a critical mass of advertisers who were willing to pay to reach the Phoenix’s young, alternative readership?

Carioli disagreed with the premise of the question, saying that Boston’s alt-culture continues to have a strong activist base and a thriving underground music scene. He praised public radio and scrappy publications like Dig Boston which to provide a space for non-mainstream voices, despite the terrible economic climate for the industry.

And, despite the fact that he recently took a job as the executive editor of Boston Magazine, Carioli will forever miss the outlet that launched his career. “There was no greater place on earth to learn your craft,” he said. “That sort of apprenticeship…. where people tell you what to read and what to listen to…really helped me become the critic that I am today.”

Questions and Answers

An audience member suggested that its transition at the end from newsprint to glossy magazine signaled the death of The Phoenix, as it became more of a “yuppie” publication. Portland and Providence versions of The Phoenix continue to run in their original format and are doing well even today. Why is that?

Alt-weeklies in smaller cities seem to have an easier time surviving than in big cities, said Carioli. There is less competition and less pressure to adhere to new advertising models in the context of a smaller community. “You see this trend in the south, you see it in Portland, and you see it in Providence,” said Carioli.

Forum director David Thorburn asked the panelists to talk a bit more about the ways in which The Phoenix differed from The Boston Globe and other mainstream publications. One important difference, already mentioned by the panel, was The Phoenix’s openness to popular culture. What other features made it truly alternative?

Pierce said The Phoenix’s alt-quality was located in both its literary, New Journalism-inspired style and in the kind of stories covered. He cited George Kimball, Dave O’Brien, and Neil Miller, who covered the AIDS epidemic before any of the other major newspapers, as examples of writers who wrote pieces on edgy topics and in an edgy style that you would be hard-pressed to find in a major newspaper.

Diamant added that The Phoenix ethos encouraged writers to take the time they need for reporting and research and gave them “a lot of space to say what we wanted.”

Rekha Murthy, a Comparative Media Studies alum now working in public radio, said she believed there was an audience for local, community-based media. She wondered if radio and the Internet are potential spaces where a Phoenix-like publication could live on.

Diamant replied that she’s very excited about the potential of local media, and thinks that radio tailored to a specifically Boston audience, like WBUR, continues to play an important role in the life of the city. She also thinks that venues like WBUR are important as a source of minority voices.

Nothing has replaced The Phoenix, she said, but if its experimental and iconoclastic spirit does rise from the ashes, it will happen not in print but in cyberspace.

Liveblog

(By Heather Craig, Chelsea Barabas, and Yu Wang, CMS ’14)

We’re at the MIT Communications Forum, where a panel is discussing the legacy of the Boston Phoenix. The Phoenix – a cultural force and a vibrant source of information – announced it was closing last March. The panelists are Anita Diamant, Charles Pierce, Lloyd Schwartz, and Carly Carioli. Seth Mnookin is moderating.

carly carioli, boston magazine

anita diamant, author (the red tent)

charles pierce, esquire, npr

lloyd schwartz, umass-boston, npr

author and essayist

Anita Diamant’s writing career began in Boston in 1975. As a freelance journalist, she contributed to local magazines and newspapers, including the Boston Phoenix, the Boston Globe, and Boston Magazine, branching out into regional and national media, with articles in New England Monthly, Yankee, Self, Parenting, Parents, McCalls, and Ms.

Staff(?) of Esquire and NPR and a staff writer with the Phoenix in the 1980s and ’90s

He has been a writer-at-large for a men’s fashion magazine, and his work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, the LA Times Magazine, the Nation, the Atlantic, Sports Illustrated and The Chicago Tribune, among others.

Carly Carioli

Seth opens forum. Explains that there are an incredible number of brilliant Phoenix alumni and it’s difficult to select just a few to come speak.

He introduces the panelists:

- Lloyd Schwartz, prof. in U. Boston, who worked at the Boston Phoenix starting in the 1970s.

- Charlie Pierce, who is the author of four books and has written for various publications.

- Carly Carioli, who was at the Phoenix since starting as an intern and was eventually the editor. He is now at Boston Magazine.

- Anita, who has written for many publications including the Phoenix. writing in boston magazine

Seth: I want to start with Carly, because you were there at the end. Were you surprised? What’s the change of format?

Carly: I guess it was September of 2012 when we were given the ultimatum to turn the newspaper into a glossy magazine in 6 weeks. Finances weren’t great and had survived downturns. As kind of a last ditch attempt to revive the brand we decided to combine Phoenix with our other publication into one glossy magazine. So the magazine came out and we were proud of it. People seemed to like it. We understood that it was an experiment and we had a limited amount of time to make it work. The reason it wasn’t a total shock because the advertising wasn’t there and the magazine was getting thinner and thinner. Ultimately the advertisement just wasn’t there.

Seth: The news that was being covered was distinct from the other news being gathered locally. Can you talk about that?

Charles: I wrote for news sections and I thought we were the first generation of the long form pieces of journalism. When I got there in 1978 it had carved out a niche for this type of work. I wrote long impressionistic pieces from campaign trails, etc.

That’s what I came there to do and that’s what we did. Hardly anyone else was doing this.

Anita: I started out in the style section and filing photographs, which was how most women got started at that time. I started writing and I was offered a column where i got to write whatever I wanted. The freedom was remarkable. Our interest was in reinventing the women’s pages (“the soft stuff” like women’s health, fashion, etc.). It was solid jounralism and the lifestyle section was solid and had news in it.

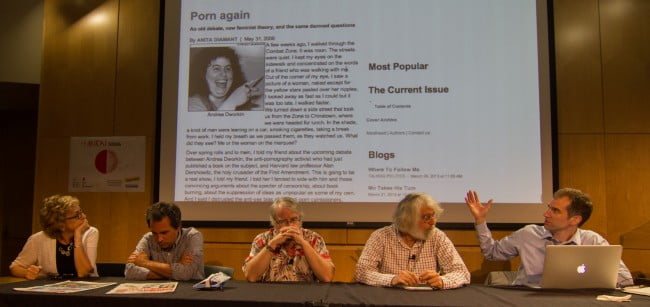

Seth: [Seth pulls up an article called “Porn Again” where Anita addresses seminal feminist questions.] So we’re talking about how the Phoenix was doing long form work. Was this something that you would see covered in other sources?

Anita: No, I don’t think so. We did many more inches than, say, The Globe. Part of what we did in the lifestyle section was take issues of women’s right and wrote about it in a way that gave it more legitimacy.

Charles: There was almost no opinion spaces in Phoenix then. There was no faux-balance. Our politics were left, no question about that, but we worked with conservatives also. We were never going to agree with these folks, but they would return my phone calls.

Seth: Anita, your piece didn’t try to hide the facts, but the Globe presented the situation in a very different way.

Anita: Allen was an asshole. And everyone reacted. I had to support my opinions with reporting. I needed to get quotes and other citations to support my statements. This is something I don’t see as much these days.

Charles: we had tremendous editors. I’ve worked with plenty of publications with several different editors, and nobody worked me as hard as the guys at the Phoenix. It was a gauntlet.

Seth: Lloyd, a lot of people saw the arts coverage as one of the defining features of the Phoenix. It wasn’t enough to be interested, you had to have a deep well of knowledge to be able to criticize it.

Lloyd: This is true and partly because there was so much space available.

Steven Shift, did go on for forever, He was notorious for talking about a new film that would take up 3 entire phoenix pages, and that in a day when Phoenix was quite big. No one was given a space limit. This was an amazing kind of freedom to have. I don’t think anyone took advantage in a bad way. We had the best rock critics in the country.

Carly: There was no better place to learn and to have people tell you what to read, what to listen to. Your daily life was reading and talking about the arts.

Charles: I came to the Phoenix after working at the Herald, where I had no space and had to turn in reviews without thinking about them. And I was butchered by the weekend editors. That was my apprenticeship. And then coming to the Phoenix where I was asked to write about music. And then the editors gave me serious attention. Those opinions of the people writing about the arts were not necessarily the most popular opinions out there. Even the Globe—and there were very good critics at the Globe—there was pressure from the top to be careful about what you said about the major institutions. And that was not the case at the Phoenix.

Seth: We will all miss the Phoenix and it’s role in our lives, but what will we actually be missing, especially given the transition to digital?

Charles: You will be missing really brilliant writers and really serious editors. That won’t be on internet.

Carly: There was a ton of stuff. There were voices that I cared deeply about that you won’t see anywhere else in Boston. Some of our groundbreaking writers are doing incredible work in other places, but not in Boston.

Seth: But is this material available to an online audience?

Carly: Yes, but is that sustainable? Will people get paid enough for it to be sustainable.

Seth: Anita you said you weren’t a reader of the Phoenix recently, why was that?

Anita: Part of it was that I aged out. Then the internet came about, but what is missing is an address to find all this stuff. An address to find Lloyd’s work, etc. Internet is a baby and we have no idea how we will be able to find content in the future and it won’t shake out for some time. It’s challenging to find strong long form content,

Lloyd: Almost all my work is online now. I work in a world of very young people. I haven’t had an editor who is 30 years old. For me the most valuable part of being at the Phoenix was learning about the field. I see sort of lacking in web journalism, In Phoenix I know what I need to know to finish a career

Seth: The attitude of Phoenix shifted to a more mainstream approach. What was lost in that transition? Are we seeing, with the passing of the Phoenix, the edges being shorn off of what we once saw as alternative culture and being repackaged for mainstream America?

Carly: Part of the constant presence of the Phoenix is that it was constantly re-inventing itself. A lot of the things that people sort of identify with the old phoenix evolved also. There are things more profitable than underground culture.

Seth: One thing that Ph was able to seize was a part of Boston and life that you wouldn’t see in the Globe because it made people uncomfortable. Now, there aren’t any areas in the city today where you feel like you need to cover your kids eyes.

Are there things that the Phoenix was covering that noone else was covering?

Chris (audience member): I worked at the Phoenix since 2008 and there are so many stories I still want to write. Other magazines probably wouldn’t print it.

Anita: I have a 27 year old daughter who does not pick up a phyical paper. There’s room. But the question is how do we create a Phoenix-like world through different channels?

Carly: The Phoenix had everything that was happening in Boston. It has been disaggregated on the internet, and there is no single place to find out what is happening.

Charles: I just wanted to read something meaningful on Phoenix at Thursday then. There is something irreplaceable when Phoenix cease to exist.

Audience member: How could this structure come together on the internet? Boston has this urge to become great again. The idea is this: Go to John Henry, suggest creating a different version of the Boston Globe.

Carly: The irony is that’s what boston.com hired me to do after the Boston Phoenix ended. It’s an enormous job to do for years on end. John Henry is a rich person who could subsidize something, but those people are hard to come by.

Audience question: How can there be Phoenix’s (Portland, Providence) in other places but not in Boston?

Seth: Smaller cities are having an easier time sustaining alt weeklies than big cities.

Carly: I was on the board of directors for the alt weekly national group. A big trend we see is that the small/medium markets the papers are becoming the papers of record. I underestimated the importance of what was “not” there when we switched to glossy magazines. People were quite attached to the fact that the Phoenix wasn’t a glossy product.

Audience question: What really made the Phoenix so alternative?

Lloyd: nobody write sports like George Edward Kimball. It was non-mainstream style, non-mainstream vocabulary. The basic journalism was solid, but the approaches to stories was unique.

Anita: there is just no space in the Globe.

Audience question: I work for a local public radio station and I think local media gets too little respect. When do you reactive Phoenix? How do you get appetite among readers?

Anita: I’m big fan of local media. I’m also a big fan of Tell me More, a show about minority voices hosted by a woman. So I’m very excited about local radio. I’m still hungry for someone to start a local website. Something like “Boston After Dark.”

Anita: The nostalgia here has to be tempered by how much we were getting paid and why people had to leave.

Audience question: I walked into the Phoenix and asked if I could write and they paid me to write a story. I couldn’t have walked into any other publication and gotten paid to write.

Stephen: Only 3 or 4 Pulitzer prize winners have won for their work on an alternative weekly.

Audience member asks question about craft

Stephen: Promoting a writer to be an editor is like promoting a gardener to be a plumber. I admire brilliant editors who are able to edit extremely well and keep the voice of the writer.